Field Office in Kiev

Developing confidence,

step by step

An incredible amount of research material; differing legal systems and initial unfamiliarity with each other. Despite this, both Australian and Dutch members working in the Field Office in Kiev have managed to build good relations with each other and with the Ukraine to effectively conduct the investigation into the MH17 crash.

In an office building in Kiev, Australian and Dutch investigating officers are working in cramped conditions in a small room. The working conditions are far from perfect, but the small room has a great advantage: the investigating officers cannot possibly get round each other.

They are professionals who recognize each other’s love for the police work. They understand each other’s circumstances. And they are, regardless of their country of origin, motivated to do their utmost to uncover the truth.

“That is why we joined the police”, says Andrew Donoghoe, a Detective Superintendent and the Senior Investigating Officer from the Australian Federal Police (AFP). He leads a team of 15 people in The Netherlands and the Ukraine, among whom include investigators, forensic specialists and intelligence analysts, “As police we quickly appreciate each other’s skills and experience, and understand how and why we are doing this work.”

June 2016

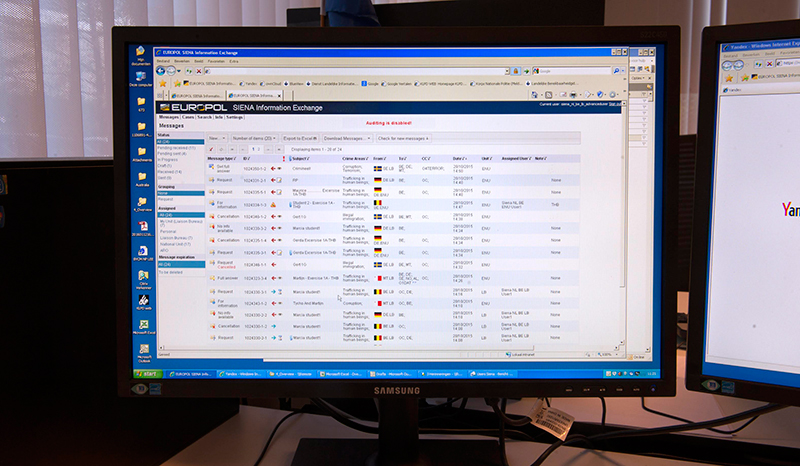

The Europol Siena program (Secure Information Exchange Network) was chosen for the exchange of information in the JIT. With this system files can be shared securely, quickly and safely by all countries involved in the investigation.

Tapped telephone conversations

Beyond the investigation area of the MH17 investigators office is a long narrow room filled with desks, after which there is another small room. Not exactly a room like you may imagine on the basis of the name “Field Office”, but still, it is the name used for this accommodation.

Since the first week of September 2014, investigating officers from The Netherlands and Australia have worked here. They work in close cooperation here with the Security and Investigation Service of the Ukraine (SBU). Immediately after the crash, the SBU provided access to large numbers of tapped telephone conversations and other data.

Russian-speaking investigating officers

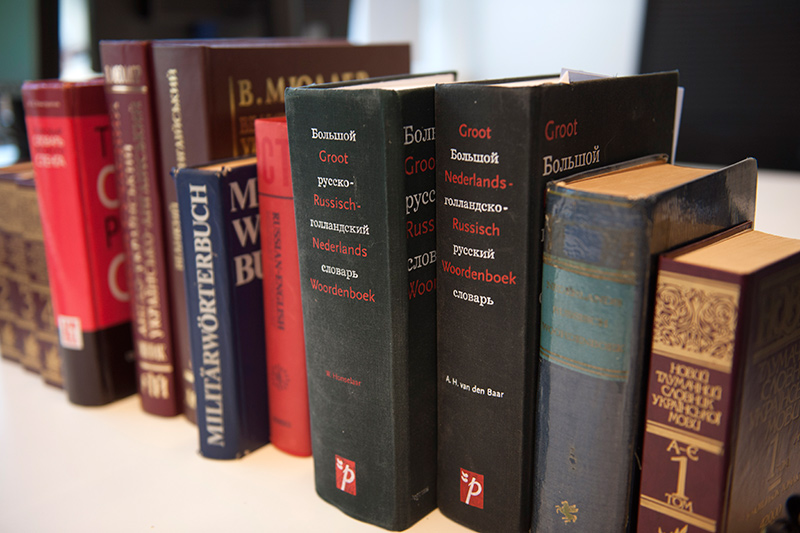

Both the Australian and Dutch police identified Ukrainian and Russian-speaking police officers amongst their personnel to work in the Field Office. These investigating officers listen to telephone conversations in order to classify the importance of the material. They also search through audio recordings with special computer programs for the name of the airplane and other important search terms. Locally recruited interpreters translate all relevant conversations into English, the working language of the Joint Investigation Team (JIT).

“We really have to pick out the scraps”, says Gert van Doorn, who, on behalf of the Dutch police, set up the Field Office in Kiev. “For example, someone mentions the names of his children in a telephone conversation. With that, we can try to identify this person. We are glad about that, but obviously all this is still very time-consuming.”

The many dictionaries are indispensible. Especially the specialist dictionaries about, inter alia, different military terminology and translations of the criminal and military laws of each country.

More and more flexible

The amount of data surrounding the time of the crash is enormous. Therefore, the Dutch offered to send their own specialists to Kiev to analyse the data with special programs.

Quickly, the analysis techniques from The Netherlands proved to be of a much higher level than those of the Ukraine. “The systems the Dutch investigators use to handle and interrogate ‘big data’ are exceptionally good”, says Donoghoe, “this is the best standard of all countries concerned, so all of the other teams have accepted that as the standard for this investigation.”

At first rather formal, cooperation with the SBU became more and more flexible. “In particular because of the data analysis, we were able to prove our added value”, says Van Doorn. “Since then, we notice in all kinds of ways that they deal with us in an open way. They share their questions with us and think along as much as they can.”

In the Field Office Dutch and Australian detectives work closely together with Ukranian detectives and the public prosecutor. Pictured here, from the upper left to the lower right:

D. Fedirko (Investigating officer with the SBU), D. Ziuzia (Investigating officer with the SBU),

I. Yanovskyi (Investigating officer with the SBU) and O. Peresada (Prosecutor of the Prosecutor General 's Office of Ukraine).

Cross-checks

With the tapped telephone conversations from SBU, there are millions of printed lines with metadata, for example, about the cell tower used, the duration of the call and the corresponding telephone numbers. The investigating officers sort out this data and connect it to validate the reliability of the material. When, for example, person A calls person B, it must be possible to also find this conversation on the line from person B to person A. When somebody mentions a location, that should also correlate with the cell tower location that picked up the signal. If these cross-checks do not tally, then further research is necessary.

By now, the investigators are certain about the reliability of the material. “After intensive investigation, the material seems to be very sound”, says Van Doorn, “that also contributed to the mutual trust.”

26 hours flying time

There are some circumstances that still make the investigation difficult and time consuming. First of all, there are all kinds of practical issues connected with international cooperation.

For instance, a solution had to be found for access to joint computer networks and contacts with each police force. The Australian investigators find themselves a 26 hour flight away from their home country and have to deal with a large time difference. “For us Australians, it is more difficult to get into contact with our home base, which is why our operation is quite isolated in Kiev”, says Donoghoe.

Also arrangements needed to be made regarding procedures, administrative processes and witness hearings. Although Ukrainian, Belgian and Dutch legal systems do not vary very much,there are large differences with Australia’s legal sysyem, which works in accordance with the Anglo-Saxon ‘Common Law’ system. “Here we have agreement amongst the JIT countries to use the system or procedure with the highest standards; this produces the least risk with future legal action”, says Donoghoe.

“The thing is to see how you can keep it workable”, says Van Doorn, “we like practical solutions. That means “poldering” [the Dutch practice of policy-making by consensus].

Eureka moment

Every morning, a minibus brings investigating officers from the hotel to the Field Office and back again in the evening after their long days. In the meantime, the investigating officers make various interesting discoveries. Every time persons or locations are identified, they experience a eureka moment, especially if after several checks all data prove to be correct.

“This is the most complex and difficult investigation I have ever been involved with in my police career”, says Donoghoe, “but we are all extremely motivated to do the best investigation possible. We won’t stop before the perpetrators of this tragedy can be brought to court.”

Field Office in Kiev

Every day in the Field Office in Kiev, investigating officers from Australia and The Netherlands work on the criminal investigation into MH17. There are four investigating officers from Australia, who are stationed in Kiev on three month rotations. The Dutch police have two teams of about five people, who rotate in and out each fortnight. Furthermore, six interpreters from the Ukraine are also active, translating all relevant material from Russian or Ukrainian into English.

The investigating officers are engaged in the identification of people in telephone conversations and from visual material, information exchange with The Netherlands and telecommunications analysis. In addition, the investigating officers have carried out more than 80 witness hearings.

The investigation must provide conclusive evidence about circumstances and perpetrators. Every possible scenario is investigated. Conclusive evidence should exclude every possibility for reasonable alternatives.